An article from The Chronicle of Higher Education has been making the rounds this week, authored by professor of psychology Gail A. Hornstein. To quote Alice Wong of the Disability Visibility project, Hornstein’s piece – titled “Why I Dread The Accommodations Talk” – is, well, “a dumpster fire of an article”.

Professor Hornstein teaches at Mount Holyoke College, a liberal arts college for women in Massachusetts. According to the college’s website, “Mount Holyoke women build robots, stand for social justice, and climb mountains”, and the college asks only that their students be “smart, determined, and willing to embrace change”. Nowhere on their website do they state the fine print: that their students are expected to be abled, or at least to overcome the infrastructural challenges of disability alone and without support from their tertiary educators.

Hornstein’s complaints are nothing we haven’t heard before. She begins the article by describing a disabled student of hers: “not confrontational, but not exactly friendly, either”; wearing an “old black motorcycle jacket and punk haircut”, “avert[ing]” her gaze”, speaking in “a flat tone”, and “mumbl[ing]”. In contrast, Hornstein “relaxes into [her] chair” and “look[s] directly” at her student. If Hornstein is sharing these details in an effort to humanise her student, she fails miserably: this is a textbook stigmatised description of millennial mental health. We know that the issue in question is mental health and not physical because that’s the point of Hornstein’s article.

Although in the USA students are not legally required to disclose their disabilities in order to receive ADA-mandated accommodations, Hornstein takes it upon herself to outline the ways in which “mental-health [sic] problems differ from many physical disabilities”, are dealt with in “overly broad and vague criteria”, and are “variable” (Hornstein seems unaware that physical disabilities are also frequently variable).

Perhaps Hornstein hasn’t read the sections of the ADA relating to eligibility, in which “disability” is defined as

A physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of such individual.

The definition of “disability” shall be construed broadly in favor of expansive coverage, to the maximum extent permitted by the terms of the ADA.

(1) Physical or mental impairment means:

-

- (i) Any physiological disorder or condition, cosmetic disfigurement, or anatomical loss affecting one or more body systems, such as: neurological, musculoskeletal, special sense organs, respiratory (including speech organs), cardiovascular, reproductive, digestive, genitourinary, immune, circulatory, hemic, lymphatic, skin, and endocrine; or

- (ii) Any mental or psychological disorder such as intellectual disability, organic brain syndrome, emotional or mental illness, and specific learning disability

(2) Physical or mental impairment includes, but is not limited to, contagious and noncontagious diseases and conditions such as the following: orthopedic, visual, speech and hearing impairments, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, intellectual disability, emotional illness, dyslexia and other specific learning disabilities, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection (whether symptomatic or asymptomatic), tuberculosis, drug addiction, and alcoholism.

(3) Physical or mental impairment does not include homosexuality or bisexuality.

Hornstein then escalates the matter even further: “faculty members”, she writes, “need to respond appropriately and help students to learn what’s a crisis (and what’s not), and to understand when it is reasonable to ask for the course structure to be changed or for expectations to be modified (and when it’s best to try to cope on one’s own).”

Let’s allow that to sink in for a moment. Hornstein’s student has come to her with legally-issued accommodations for a documented mental illness. For those unfamiliar with the process of diagnosing, documenting, and requesting accommodations for mental health conditions, I can tell you now that it’s hellish. Any student who has access to disability accommodations has already been through an absurd amount of diagnostic bureaucracy in order to get to that point – bureaucracy that’s made even harder if, for example, you have a disability that interferes with your executive function, ability to make or keep appointments, capacity to make phone calls, chase up referral forms, or explain intimate details of your life to various medical and authoritative bodies.

Hornstein’s student’s request is very simple: she has panic attacks and has been granted extended deadlines in the event that her disability interrupts her studies. This is in accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, which states that:

Any private entity that offers examinations or courses related to applications, licensing, certification, or credentialing for secondary or postsecondary education, professional, or trade purposes shall offer such examinations or courses in a place and manner accessible to persons with disabilities or offer alternative accessible arrangements for such individuals.

…Any private entity that offers a course covered by this section must make such modifications to that course as are necessary to ensure that the place and manner in which the course is given are accessible to individuals with disabilities.

Unfortunately for Hornstein’s student, instead of reassuring her that her disability accommodations will be provided as is required by law, Hornstein – rather bafflingly – explains that her course has a “fast pace” and that her student would “be at a significant disadvantage if [she] missed a test”. (…Rather the point of needing legal accommodations, no?) Instead of telling her student that she will comply with the law, Hornstein says that she does not provide make-up exams in her course, and asks what might be the most insulting question ever asked of a student with panic disorder: “What do you usually do to calm down before an exam?”

“What do you usually do to calm down before an exam?”

Yikes.

If I were Professor Hornstein’s student, and in response to my request for legal accommodations she had asked me, essentially, “Have you thought about calming down?”, I may well have laughed in her face. Or quit the course right there. Or reported her to my university’s Disability Support Services.

Anyone who has documentation and accommodation requests has already got all the coping skills, all the strategies, all the tools, & they’re damn resilient just to get that far in the first place. It’s condescending and a fundamental misunderstanding of the way panic attacks work. Like – oh shit, it hadn’t occurred to me to just STOP being mentally ill! No one’s ever suggested that before! So fucking helpful!

I’ve been having panic attacks since I was a child. I’ve been getting psychiatric and psychological help for them for the last five years. I still get panic attacks. Sometimes they occur in response to easily-identifiable stimuli and sometimes they come seemingly out of nowhere. My heart beats irregularly and very fast, I experience dyspnoea (shortness & irregularity of breath), my whole body breaks out in a sweat, I have hot and cold flushes, my chest feels tight and painful, I might blush bright red or go dead pale, I shake like a stick insect in a hurricane, I feel numb, dizzy, tingly, my throat feels choked, my limbs feel weak, sometimes my vision goes dark or blurry, I feel nauseous and sometimes throw up, and I often experience dissociation, derealisation, or depersonalisation. Usually I end up sobbing my guts out.

Like many people who experience panic attacks, I often worry about “losing control” or “going crazy” (note: “crazy” is often considered a slur, or at least a remarkably rude descriptor, in neurodivergent communities). Unlike many people who experience panic attacks, I am lucky enough that I have never mistaken a panic attack for a heart attack – possibly because I have actual heart attacks to compare them to (I have a bicuspid aortic valve and an ascending aortic aneurysm, and have frequent emergency episodes of various kinds of cardiac nonsense.) For Professor Hornstein’s benefit, I can quite happily report that panic attacks can be every bit as debilitating, painful, and terrifying as heart attacks. Sometimes my panic attacks last under a minute, and sometimes they can last hours. Generally they will last between twenty to forty minutes. (For those who might find it useful, you can download a copy of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale here, and you can access the Panic and Agoraphobia Scale here.)

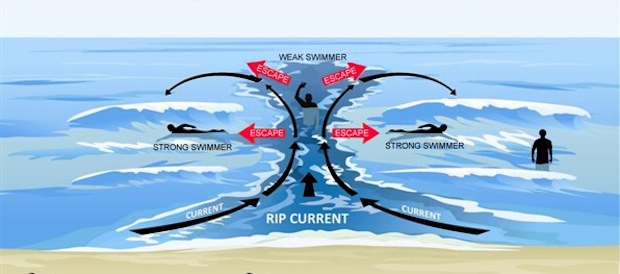

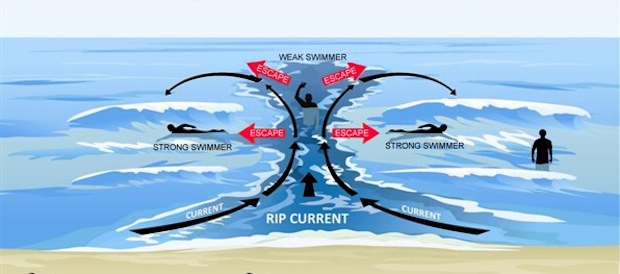

Once I am in the throes of a panic attack there is very little that I can do except ride it out. In that respect they’re very much like rip currents. Rip currents are narrow, extraordinarily powerful currents that are easy to spot if you know what you’re looking for, but fiendishly difficult to recognise if you don’t. My mother volunteered as a lifeguard when we lived on the coast, so for a couple of years every Sunday my siblings and I were enrolled in the junior surf lifesaving program. There are three ways to escape a rip: swim between the flags where the lifeguards are watching, hold your arm up straight & wait to be rescued; swim sideways away from the pull of the water, parallel to the beach, until you escape; or relax, keep your head above water, and wait for the current to eventually bring you back to shore. The worst thing you can do if you’re caught in a rip is panic and try to swim straight back to shore; the rip will pull you rapidly away from the beach and you’ll exhaust yourself trying to fight the tide. Rip currents kill more people on average in Australia than bushfires, floods, cyclones and sharks combined.

[Image description: anatomy of a rip current, with routes of potential escape.]

Hornstein is the lifeguard here. Her student was caught in a rip current and held her arm high for assistance, as she should be able to expect when swimming in a lifeguard-patrolled area. And yet instead of paddling out to rescue her, Hornstein left her student to fend for herself, with the justification of encouraging strong swimming. But not everyone is a strong swimmer, and you don’t become a strong swimmer by flinging yourself into a rip and hoping for the best.

According to Hornstein, her student’s response was as follows:

She mumbled a few things, and we talked a bit longer, but little concrete guidance emerged.

The term moved along, and I saw her each week in the back row of the lecture hall, but she never again came to my office. The TA of her lab section said Lee never missed a deadline and was doing well. I didn’t give her specific advice, nor did I ignore the reality of her problems. Instead, I conveyed confidence in her capacity to succeed and to come up with strategies to manage her difficulties. I have no idea if she still suffers panic attacks, but she didn’t miss any deadlines and got a high grade in my course.

It sounds like Hornstein’s student made it out of the rip alive – maybe because she’d been caught in rips before and knew what to do, or because a nearby swimmer noticed her distress and helped her out. Maybe she gave up and relaxed into the current, hoping to at least stay awake & above water for as long as possible, only to get lucky and be brought back to shore by happenstance, depending on the shape of the beach. Either way she was put in a terrifying position, denied legal aid, & forced to struggle her way out while being told it was building moral fortitude. Hornstein counts this as a success. But how many other students have drowned?

You can’t fight the whole ocean alone.

Hornstein, naturally, is convinced that her negligent approach is actually what’s best for her students. She describes herself as “an outspoken ally of many disability-rights activists” who has “taught and written about mental health for 40 years”. And yet she continues to betray her lack of understanding or compassion toward disability & disabled lives with every subsequent paragraph. Frankly, if this is the mindset of the last 40 years of mental health academia, no wonder it’s in such a sorry state.

“People have the right to behave oddly”, she claims, and as an example: “I once had a student who did not look directly at me or any other member of that 15-person seminar for the entire semester. I’ve had students who made strange head movements in class because they were hearing voices.”

This is not “behaving oddly”. It’s deeply, insidiously ableist that Hornstein was examining her students’ body language to this degree in the first place, that she considers this worthy of note, let alone that she considers herself super progressive for tolerating it. A very common hallmark of autism is significant discomfort making eye contact. ABA (Applied Behaviour Analysis) therapy, which has been rightfully called out in many forums as being horrifyingly abusive, holds forced eye contact as one of its main tenets. Sparrow Rose at the blog Unstrange Mind describes witnessing an instance of ABA therapy in action outside a behavioural clinic:

A mother and father came out of the clinic with a little girl, around 7 years old by my best guess. Mother said, “Janie (not the actual name), look at me.” Janie didn’t look at her mother. The mother said to the father, “you know what to do,” and the father took hold of Janie and turned her head toward mother, saying, “look at your mother, Janie.” Janie resisted, turning her head away and trying to pull out of her father’s hands.

Mother crouched down and Father lifted Janie’s whole body up, laying her across Mother’s knee, face up. “Look at your mother, Janie,” father said. “Look at me, Janie,” Mother said. Janie began to whimper. Her body was as stiff as a board. Father held her body firm and Mother took hold of Janie’s head, “look at me, Janie,” Mother said.

I was glued to the sidewalk. I didn’t want to see any more but I couldn’t look away, couldn’t walk away. Janie began to moan and thrash her body. Father’s hands held her body steady as she kicked and flailed. Mother’s hands held Janie’s head steady. Both kept urging Janie to look at her mother. Janie’s moans turned to screams but neither parent let her go.

Finally, Janie’s entire body went limp with defeat. She apparently made eye contact because Mother and Father began to lavish praise on her. “Good girl, Janie. Good eye contact. Good girl. Let’s get some ice cream now.” Janie’s limp body slid to the sidewalk where she lay, sobbing. Father picked her up and carried her to the car, the whole way praising her submission. “Good eye contact, Janie.”

I hate making direct eye contact. It makes me feel queasy and hypervisible, like a stranger holding a hug for too long. I can fake it enough to get by but it’s unpleasant. I feel very sad at the thought of my lecturers taking note of whether or not I am making eye contact and concluding that it’s “odd” but something they are reluctantly willing to tolerate. Autistic ways of being in the world aren’t “odd”. The student in question might have been autistic, or they might have had social anxiety, or they might have been shy, or they might just have not wanted to make eye contact. Regardless, policing body language in this manner is a manifestation of systemic ableism.

Hornstein’s second example is equally infuriating – what, to her, constitutes “strange” head movements? And how in the hell did she come to the conclusion that those “strange head movements” must have been because the student was experiencing auditory hallucinations? Why did Hornstein phrase it as “hearing voices” rather than “auditory hallucinations”? Why did she feel the need to specify at all?

She provides concrete examples of situations that she considers “serious” and “not serious”. “Not serious” conditions include: headaches, colds, “being anxious about the assignment or having a minor conflict with a roommate”. “Serious, unexpected circumstances” include: “coming down with the flu or experiencing the death of a close relative… staying up all night with a suicidal friend or having an exam the morning after a distressing break-up.”

It doesn’t escape me that all of her examples of what actually constitutes as “serious” in her eyes are things that affect abled people. Having the flu, experiencing the death of a relative, staying up with a suicidal friend. What if I’m the dying relative? What if I’m the suicidal friend? What if a cold is just as debilitating for me as the flu? For that matter, what if I am immunocompromised and fellow students coming to class with “not serious” colds pose a significant danger to me? What if my anxiety and agoraphobia are so intense that they prevent me from leaving the house for weeks at a time? What if my migraines are so gut-wrenchingly painful that I can’t speak, see, hear, or move? All of these are things I have experienced in an education context. For the most part, as with Hornstein’s students, I have been left to make my way out of the rip alone.

Hornstein believes that “people have to learn to manage chronic problems and conditions, and to cope with the crises — be they physical or emotional — that can affect any of us at certain moments.” Except Hornstein hasn’t been affected by chronic conditions, or by physical or emotional crises: she writes that “For some people, school is a refuge, a conflict-free zone where they can relax and be successful. (I know; I was one of them.)” It’s easy to advocate for strength when you haven’t had to be strong. And of course it’s beneficial for people experiencing hardship to learn fortitude and resilience, but they’ll be doing that already, on their own terms, and they shouldn’t have to face infrastructural obstacles in tertiary education for the sake of building character. Regardless of Hornstein’s opinions about strength in the face of adversity, making the conditions of her students’ education more adverse is not the solution, especially when this logic is applied only to disabled students.

Hornstein calls this “crucial life lessons of adulthood”, and cautions against “overprotecting” students. She considers her authoritative capacity as a teacher to include “determining who actually requires assistance, and in what form, and discouraging students from defining themselves by what they can’t do”.

I would posit that it’s a lot easier to avoid defining yourself by what you can’t do if you live in a world where “what you can’t do” doesn’t have such an enormous definitional capacity toward your identity. I can’t breathe underwater and I can’t speak medieval Latin, but those things don’t prevent me from accessing education on the same level as my peers. If my teachers were regularly asking me “but have you just tried harder to breathe underwater?” then perhaps my lack of amphibiousness would seem more immediately relevant.

Hornstein ends the article with these parting lines:

Lee’s accommodation letter did serve one key function: It gave her permission to meet with me and to reveal, if she so chose, potentially embarrassing private information that she would not otherwise have told a professor.

And it gave me a chance to model an attitude of nonjudgmental assessment of the circumstances, and to encourage self-reliance, coping skills, and confidence in a student’s strengths and talents.

It’s not embarrassing to be disabled and seek legal accommodation.

It’s not good teaching to “nonjudgmental assess” (…ie… nonjudgmentally judge???) circumstances that aren’t your job to assess, & then to essentially say “your panic attacks are a weakness & character flaw that you can overcome by Coping and being Self Reliant”.

I don’t know what hardships Professor Hornstein has experienced in her life. Regardless, her hardships are not everyone’s hardships, and her coping strategies are not everyone’s coping strategies. In writing this article she has not positioned herself as a disabled person, a mentally ill person, or a person facing adversity in any form; she has positioned herself as “a professor of psychology at Mount Holyoke College” and “an outspoken ally”.

It’s not up to teachers to decide how or when the ADA should apply to their students. The point of the ADA is that it applies to everyone, all the time. Anti-discrimination legislation exists to remove structural barriers. If Hornstein is concerned about her students’ ability to face adversity later in life, she should put her energy towards eradicating the conditions and causes of that adversity, not just encourage her students to get used to it early.

It’s not up to people who do not need assistance to decide “who actually needs assistance, and in what form”. Disability accommodations provide equality, not advantage. If our efforts to remove disadvantage overshoot the mark and advantage certain groups to the detriment of others, then we can tackle that issue as it arises.

It’s not up to abled people to make moral judgements about disabled people’s lives, experiences, body language, ways of coping with adversity, or the avenues of legal aid that they choose to employ.

To those fighting the rip alone: I’m so sorry. It’s rough and I’ve been there. It’s so hard to keep going when you’re scared, lost, in pain, and can’t see the shore. But rips are only dangerous if you don’t know what you’re dealing with. Maybe nobody will help you, and I’m sorry for that too. I can’t promise that a time will come when you’ll be able to breathe easy. But I can damn well promise that there’s solidarity in struggle, that I won’t go quietly, and maybe if we’re lucky we’ll manage to fight our way out together.