A new collaborative article in Health and History, the journal of the Australian and New Zealand Society for the History of Medicine. Massive thanks to Effie Karageorgos for pulling this project together.

Robin Eames, Jordan Evans, Samantha Kohl Grey, David T. Roth, Lucinda Stormont-Sainsbury, Effie Karageorgos, ‘Picturing Medical Histories: “Ways of Seeing” the Historical Medical Subject’, Health and History 25, no. 2 (2023): 55–86. Available here or here (open access).

Abstract:

The image has been used by medical professionals for centuries to illustrate both usual and unusual processes of the body and mind. Images can expose or conceal medical truths, and in many cases are the only connection that exists between the historian and the frequently silent or silenced patient. In this paper, a group of historians each present and explore various methods of applying ‘ways of seeing ‘ or the ‘clinical gaze’ to a historical image from the medical world. Some images have been used to strategically serve the purposes of authority figures and silence the ill subject. Others reveal previously obscured patient’s voices. All present a perspective on the possibilities for analysing and assessing medical imagery from the past that moves beyond traditional understandings.

My section is titled ‘Dead/Effeminate’, a brief analysis of Edward Moate, institutionalised in Beechworth Asylum in 1884.

Dead/Effeminate

Robin Eames

In 1884 a man named Edward Moate, living in Bright, Victoria, was arrested on a trespassing charge initiated by his former landlady. Moate was remanded for medical examination, and a day later was rearrested on a lunacy charge. The arresting police officer, Senior Constable Edward Shoebridge, gave a deposition explaining the altered charge: he did not suspect that Moate was mad, but rather ‘was suspicious as to whether Moate was really a man’.[i]

Moate had been working as a personal manservant to a surgeon, Doctor Benjamin Warren, and living in his household. Moate had good relationships with his community, and lived a generally quiet life, despite being well-known in his neighbourhood as ‘Ned the woman’ and ‘Old Biddy’.[ii] Dr. Warren was one of two local doctors who was usually responsible for signing lunacy certificates in Bright. When he died in 1884 after a long illness, Moate was arrested less than a fortnight later. At his lunacy trial, Senior Constable Shoebridge told the court ‘that the belief entertained by him and other residents of Bright and Omeo districts was that Moate was a female’.[iii]

Moate was taken to Beechworth Police Court, examined by two doctors (Dr. Henry Fox and Dr. David Skinner) and ultimately committed to Beechworth Asylum. Sergeant Shoebridge conveyed his doubts about Moate’s gender to the medical superintendent of the asylum, Dr. Deshon, ‘and was shortly afterwards informed that his suspicions were well founded as “Edward” Moate was undoubtedly a woman’.[iv]

Officially Moate’s diagnosis was one of religious mania.[v] After Moate’s story was widely publicised around the colonies, a few articles speculated that grief over Dr. Warren’s death may have been the cause of his insanity, but this was not reflected in the actual medical process. Moate’s lunacy trial, and the notes in his patient record, fixated on his gender transgression as the proof of his insanity.

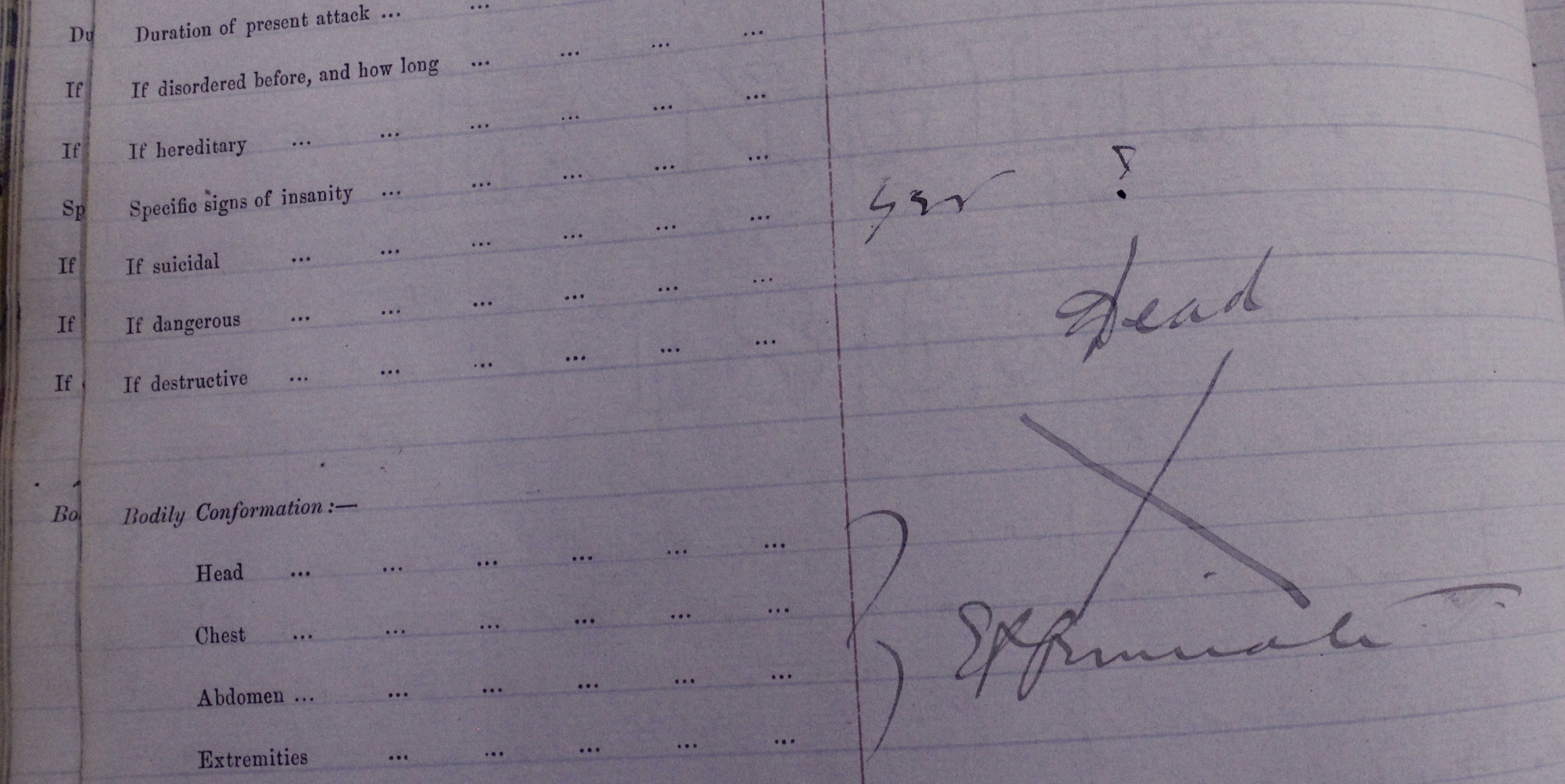

The image at the focus of this article is taken from Moate’s file in the female casebook of Beechworth Asylum.[vi] In the section of his patient record noting the physical signs and symptoms of lunacy, the only comments included by his treating physician were ‘Sex ? Effeminate’.[vii] Within the visual framing of lunatic asylum records, Moate’s perceived effeminacy became the sole justification for a diagnosis of insanity, and for his subsequent involuntary incarceration. Nancy Rose Marshall notes that in the nineteenth century ‘artists and scientists both invested heavily in the faculty of sight’; the medical gaze, like the scientific gaze, was considered an ‘ostensibly objective form of looking’; of ‘seeing rather than analysing’.[viii] As the object of the medical gaze, patients were reduced to images. Andrew Scull refers to Shakespeare’s characterisation of lunatics as ‘pictures, or mere beasts’, noting that ‘the presumed need to segregate the mad from society’ was partly driven by a desire to make the spectre of madness invisible.[ix] By re-examining the relationship between lunacy records and visual cultures, we can discover new ways of seeing through (and analysing) the archives.

Reportedly Moate’s ‘effeminate appearance’ was also the reason why Shoebridge had arrested him in the first place.[x] Despite this, the Melbourne papers reported that ‘[p]revious to the detection of her sex at the asylum, no suspicion of her singular masquerade appears to have been entertained by anyone’.[xi] Moate’s gender was in fact a matter of common knowledge in his neighbourhood; a Beechworth newspaper noted that he ‘was attired as a man, and had for several years lived as such, but was believed to be a woman’.[xii] The local correspondent for Omeo wrote that:

Her sex amongst the old residents was always a matter of doubt … She was only small, and her strength and endurance for a woman were something wonderful. In fact, she had the reputation of being a very good working man.[xiii]

This sentiment was echoed in the Omeo Chronicle by the local correspondent for Deptford, who was even more sympathetic:

I am very sorry for the misfortune that has fallen on poor “Ned Moate.” In common with others who lived on the Omeo road, I was well acquainted with him or her. Always civil, obliging and goodnatured, very honest and willing, nobody cared to press the question of sex on her, though the truth was more than suspected, it having leaked out on one of the very rare occasions, when she indulged in a glass too much. She bitterly resented any imputation on her manliness, and as she looked as like an old fashioned postboy as possible, and rode and groomed a horse well, she was allowed to have her own way unmolested.[xiv]

Gender transgression in the nineteenth century was frequently managed via vagrancy laws, but it was not unprecedented for it to form the basis of a lunacy charge.[xv] Edward de Lacy Evans, a Bendigo goldminer, had been institutionalised as a lunatic five years earlier, and discharged as cured after being forced to detransition. Indeed Moate was referred to in the papers as ‘another De Lacey [sic] Evans’ and ‘another female man’.[xvi] Moate’s lunacy charge essentially came about for two reasons: firstly because Moate had crossed gender categories in a way that violated colonial gender norms, and secondly because he had lost the protection of his employer. Moate’s strong social connections were possibly why he was arrested as a (potentially curable) lunatic patient, rather than fined or imprisoned as a vagrant, but they were not enough to prolong the tacit acceptance of Moate’s position in his community.

Once Moate became unemployed, unable to pay rent, and was no longer seen to be contributing positively to his community, he was removed via the systems that policed and punished disruptive aberrance. These systems did not render him in terms of aberrant femininity but in terms of aberrant masculinity – that is, effeminacy. According to the logic of the era, an effeminate man was a weak, inferior and unhealthy man. This was the rationale of eugenic theory, which had not yet been clearly defined in Australia but became increasingly popular from the 1890s and throughout the interwar period.[xvii] In 1884 there was already a strong perception that effeminacy was cognate with weakness, mental degeneration, and threats to white Australian futurity.[xviii] The label of effeminacy was apparently applied equally to transmasculine and transfeminine gender-crossers. In 1887, Carrie Swain was charged with vagrancy in Sydney for dressing as a woman, and described in the Evening News as both an ‘effeminate youth’ and ‘a detestable character’ who was ‘in the habit of perambulating the streets and parks after dark’.[xix] Effeminacy was also a euphemism for same-sex male attraction, which may also have been a factor in the concerns surrounding Moate:

[Dr. Warren] was parted from his wife, and it is alleged in Omeo that the “intimacy” between the doctor and his servant was the cause of the separation, the doctor when “in his cups,” having stated his preference for “Old Ned.” Some few months ago, Dr. Warren was heard to say that “to his utter astonishment, he had just found out that ‘Ned’ was a woman.” The neighbours had believed this for years, and it was a common topic of conversation over the whole of the Alpine district, from Myrtleford to Omeo, and the boys there always teazed and twitted “Ned” with being a woman. Thus no surprise is felt at the discovery.[xx]

Moate’s unsanctioned transgression of contemporaneous gender norms was nevertheless allowed to continue for twenty years. This acceptance was both conditional and limited. Unlike his contemporaries Edward de Lacy Evans and Jack Jorgensen, who worked in mining and farming respectively, Moate did not transition into the productive workforce.[xxi] In his twenty years in Omeo and Bright, Moate worked as an assistant to the clerk of courts in Omeo and as a domestic servant to a well-respected physician. Unlike Evans and Jorgensen, Moate’s labour was not considered uniquely masculine to the point of provoking anxiety, but it also lacked the redemptive qualities of producing surplus value for the colonial economy. Moate was presumably protected by the social authority of his employers, rather than by the moral and social value assigned to his employment. When that protection disappeared, Moate was exposed to the judgement of the state.

As someone who had departed from his assigned position in the gendered order, Moate was categorised as an undesirable social deviant.[xxii] He was institutionalised not so much because he was sick, but because he was regarded as sickening to society. Social disorder was therefore rendered as medical disorder in order to remove, contain, and manage the threat of slippage between hierarchical social groups.

Moate refused to provide a female name or any information about his history before arriving in Victoria. With the infamous and recent example of Evans, Moate would have known that the pathway out of the asylum required detransitioning. He refused to take that path; all of his patient records were under the name Edward Moate, and he never became compliant to the satisfaction of the asylum staff. He died in Beechworth Asylum three years after his admission, under the name Edward Moate.

[i] ‘Remarkable Imposture at Beechworth’, The Age (Melbourne), 25 July 1884, 5.

[ii] ‘Our Omeo Letter’, Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle. 31 July 1884, 2.

[iii] ‘Remarkable Case of Deception’, Weekly Times (Melbourne), 2 August 1884, 11.

[iv] ‘Remarkable Imposture at Beechworth’, The Age (Melbourne), 25 July 1884, 5.

[v] Patient record for Edward Moate. PROV, VPRS 7396/P/0001. Beechworth Asylum Case Books 1878-1892. Female casebook no. 2, entry 18, 24 July 1884.

[vi] Patient record for Edward Moate. PROV, VPRS 7396/P/0001. Beechworth Asylum Case Books 1878-1892. Female casebook no. 2, entry 18, 24 July 1884.

[vii] Patient record for Edward Moate. PROV, VPRS 7396/P/0001. Beechworth Asylum Case Books 1878-1892. Female casebook no. 2, entry 18, 24 July 1884.

[viii] Nancy Rose Marshall, ‘Introduction’, Victorian Science and Imagery: Representation and Knowledge in Nineteenth Century Visual Culture (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021), 12.

[ix] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 4 Scene 5, line 82, quoted in Andrew Scull, Madness in Civilisation: A Cultural History of Insanity from the Bible to Freud (London: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 188–190.

[x] ‘A Remarkable Case’, The North Eastern Ensign (Benalla, Victoria), 1 August 1884, 3.

[xi] ‘A Remarkable Case’, Advocate (Melbourne), 26 July 1884, 11.

[xii] ‘Beechworth Police Court’, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 26 July 1884, 4.

[xiii] ‘Our Omeo Letter’, Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle. 31 July 1884, 2.

[xiv] ‘Our Deptford Letter’, Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle. 5 August 1884, 2.

[xv] Victoria’s Vagrancy Act of 1852 was mostly inherited from British legislation. The colonial laws were vague and flexible enough to be applied mostly at the discretion of the police. See also Suzanne Davies, ‘Vagrancy and the Victorians: The Social Construct of the Vagrant in Melbourne, 1880–1907’, PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 1990; and Adrien McCrory, ‘Policing Gender Nonconformity in Victoria, 1900–1940’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 19 (2021), online. https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2021/policing-gender-nonconformity-victoria-1900

[xvi] ‘Another De Lacey Evans’, Geelong Advertiser, 28 July 1884, 4; ‘Another Female Man’, Burra Record (South Australia), 1 August 1884, 2.

[xvii] See Diane B. Paul, John Stenhouse and Hamish G. Spencer (eds.), Eugenics at the Edges of Empire: New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and South Africa (Cham: Palgrave |Macmillan, 2018), 21.

[xviii] ‘Are the English Becoming Effeminate?’, Argus (Melbourne), 4 October 1884, 4. The anxiety around degeneracy was certainly not universal, and received pushback as early as it appeared in the 1870s. See ‘“Mozeck” and Human Degeneracy’, Yorke’s Peninsula Advertiser and Miners’ News (South Australia), 30 October 1874, 3.

[xix] ‘A Detestable Character’, Evening News (Sydney), 17 November 1887, 5.

[xx] ‘A Man Impersonator’, The Herald (Melbourne), 25 July 1884, 3.

[xxi] Jorgensen was a German migrant who also lived in the Bendigo district, working as a farmer in Elmore between 1873 and 1893. He was exposed as an ‘impersonator’ after his death, and posthumously appropriated Moate’s title of ‘Another De Lacy Evans’. See ‘A German de Lacy Evans at Elmore: A Female Mounted Rifleman’, Bendigo Independent, 6 September 1893, 3. See also Lucy Chesser, Parting With My Sex: Cross-Dressing, Inversion and Sexuality in Australian Cultural Life (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2008); Lucy Chesser, ‘Woman in a Suit of Male: Sexuality, Race and the Woman Worker in Male “Disguise”, 1890–1920’, Australian Feminist Studies 23, no. 56 (2008): 175–194.

[xxii] The colonial lunatic asylum was a key structure in the policing and punishment of social deviance, alongside the courts and prison system. See also Alexandra Wallis, ‘The Disorderly Female: Alcohol, Prostitution and Moral Insanity in 19th Century Fremantle’, Journal of Australian Studies, 25 July 2019, online. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14443058.2019.1638815